Udacity Projects Series Part 1: Predicting Bike Sharing Patterns

I have had a lot of fun doing Udacity’s Deep Learning Nanodegree and would highly recommend enrolling in it. For me, the projects were the highlight of this nanodegree. From implementing a neural network from scratch in NumPy to deploying an entire model on Amazon Web Services, the projects provided a very good understanding of the different aspects of deep learning. As suggested by the fellows at Udacity and also by the seasoned individuals, I am making a habit to document my projects and learned skills. This 5 part series justifies that purpose where I write about my implementations of the projects. In the particular order, we discuss the following projects:

- Predicting Bike Sharing Patterns

- Dog Breed Classifier

- Generate TV Scripts

- Generate Faces

- Deploying a Sentiment Analysis Model

In the first part (project), we will understand and build a neural network from scratch to carry out a prediction problem on the bike sharing data. This post will help in understanding the concepts of forward pass, gradient descent, backpropagation and hyperparameter tuning from the ground up. It is essentially a predictive modeling problem where a 2-layer neural network (including the output layer) is used to predict (regress) future ridership data based on the historical data. The full implementation of the project is available here. This post is just for understanding the details.

Dataset

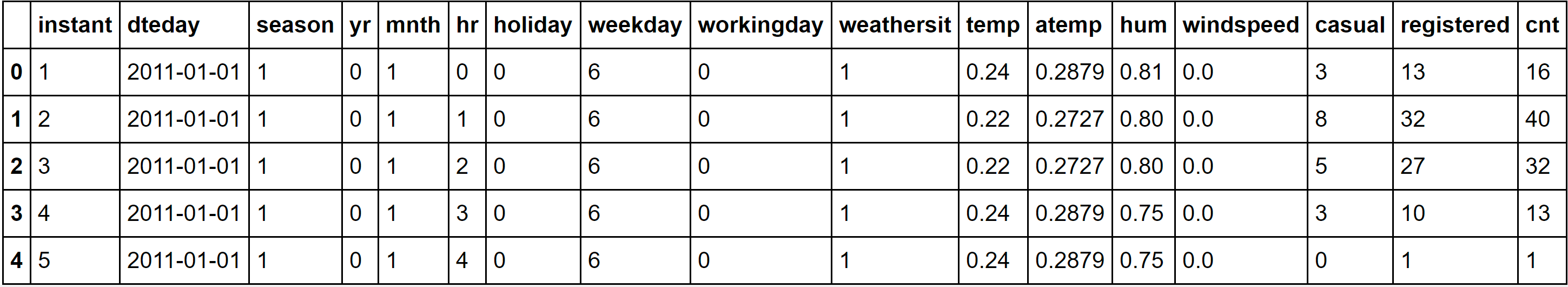

We are using University of Porto’s Bike Sharing Dataset. This dataset has the number of riders for each hour of each day from January 1, 2011 to December 31, 2012. The number of riders is split between casual and registered, summed up in the cnt column. You can see the first few rows of the data below.

The information about the different columns of the dataset can be viewed here. For our purpose, the target columns are cnt, casual and registered. The rest of the columns serve as the input features. Some of the columns have categorical values like weathersit, mnth, season, hr and weekday. We convert these into one-hot representation using Pandas’ get_dummies() method. We delete the respective columns and also some other columns which are not useful like instant, dteday, atemp and workingday.

Since the continuous variables have different scales, we need to normalize them to make the training easier. We shift and scale the variables such that they have $0$ mean and a standard deviation of $1$. For making the predictions, we store the means and standard deviations in a dictionary to reverse the normalization.

Finally, we separate the data into training, validation and test sets. We’ll save the data for the last approximately 21 days to use as a test set after we’ve trained the network. The rest of the data is divided into training and validation. Since this is time series data, we’ll train on historical data, then try to predict on future data (the validation set).

Network

Now we look into the structure of the network and how it is built to train on our dataset.

Initialization

We create a 2-layer neural network using NumPy. Of course, the network can have more depth but this is just for the sake of creating the network from scratch. To do this, we create a class and initialize it with all the necessary information - input nodes, hidden nodes, output nodes, learning rate, weight initialization.

The number of unique features we have after dropping the columns instant, dteday, atemp and workingday is 10. The one-hot representation separates the categorical columns weathersit, month, season, hours and weekday into their respective columns resulting in 56 features. This is the number of input nodes. The output_nodes is just 1 which is the number of riders. The hidden_nodes is a hyperparameter which usually lies between input_nodes and output_nodes.

We initialize the weights of the layers with a normal distribution. Good initialization results in efficient training. Here, we are using the fact that the output of a layer is a dot product between the input and weights (followed by activation):

\[y_i = \sum_{j=0}^{n-1}w_{ij}x_j\]The input has a mean of $0$ and standard deviation of $1$. If we choose the same statistics for the weight of a given node, the output of one product between input and weight $w_{ij}x_j$ would still have a mean of $0$ and standard deviation of $1$. This is helpful as further dot products in the network do not result in either vanishing or exploding products. Now the output is a sum of these products upto the number of nodes in the layer. Hence, the output will have a $0$ mean and a variance equal to the number of nodes $n$ or a standard deviation of $\sqrt{n}$. Hence, we initialize the weights with a normal distribution $\mathcal{N}(\mathbf{0},\sqrt{n}\mathbf{I})$

Forward pass

The forward pass builds the computational graph in the following way:

- $h^{\prime} = XW^{(1)}$

- $h = \sigma(h^{\prime})$

- $o = hW^{(2)}$

- $L = \frac{1}{N}\sum_{i=0}^{N}(y_i-o_i)^2 = (Y - o)^T(Y - o)$

where $X$ is the input, $h^{\prime}$ is the pre-activated hidden output, $h$ is the activated hidden output, $W^{(1)}$ and $W^{(2)}$ are the weights of hidden and output layer respectively, $o$ is the final output and $L$ is the mean squared error between the grount truth $y$ and output $o$ for $N$ records. There is no activation at the output layer since we want real values for the number of riders.

Backward pass

The backward pass calculates the gradients (partial derivates) at each layer to get the error w.r.t the different weights of the network. You might already know or have heard about the famous backpropagation algorithm. Here, we are going to see it in action.

For smaller networks like ours, it is always suggested to work out the math in backpropagation on a piece of paper. It helps to understand how the information is flowing inside the network. Specifically, for this project, it was an essential part to implement it correctly.

Before we dive in, there are two techniques by which you can calculate the gradients. There might be other techniques or algorithms but I am familiar with these two. The first is basically to compute the gradient using the product of partial derivatives (chain-rule). For example, with a compute graph like below:

\[c = a + b\] \[d = c^2\] \[e = d * f\]the gradients $\frac{\partial e}{\partial a}$, $\frac{\partial e}{\partial b}$ and $\frac{\partial e}{\partial f}$ can be written as:

\[\frac{\partial e}{\partial a} = \frac{\partial e}{\partial d} * \frac{\partial d}{\partial c} * \frac{\partial c}{\partial a} = f * 2c * 1\] \[\frac{\partial e}{\partial b} = \frac{\partial e}{\partial d} * \frac{\partial d}{\partial c} * \frac{\partial c}{\partial b} = f * 2c * 1\] \[\frac{\partial e}{\partial f} = \frac{\partial e}{\partial f} * \frac{\partial f}{\partial f} = d * 1\]This has no symbolic meaning with the network and you just need the chain-rule to get the particular gradient. However, neural networks usually have similar operations repeated in multiple layers. Each layer is characterized by matrix multiplications and an activation. It is, therefore, helpful to utilize this structure. From the Udacity Nanodegree:

Since the output of a layer is determined by the weights between layers, the error resulting from units is scaled by the weights going forward through the network. Since we know the error at the output, we can use the weights to work backwards to hidden layers.

The error at the output is simply the gradient of the loss $L$ w.r.t the output $o$. Similarly, the hidden error is the gradient of $L$ w.r.t $h$. The general algorithm used here is as follows:

- Calculate the error in the output unit, $\delta^o = (y - y^{\prime})f^{\prime}(z)$ where $y^{\prime}$ is the output, $f^{\prime}(z)$ is the gradient of the activation function and $z = \sum_jW_ja_j$ is the input to the output unit (pre-activated hidden output).

- Propagate the error to each hidden unit, $\delta^h_{j} = \delta^oW_jf^{\prime}(h_j)$ where $W_j$ is the weight between the output layer $j$ and the input layer $j-1$.

Now, let’s use these steps to compute the gradients of our network. Using the notation in the forward pass, from step 1, we have:

\[\delta^o = (Y - o)\frac{\partial{f(o)}}{\partial o} = (Y - o)\frac{\partial o}{\partial o} = (Y - o)\]since there is no (or identity) activation at the output.

Since we have only one hidden layer, we denote its error term by $\delta^h$. From step 2, we have:

\[\delta^h = \delta^oW^{(2)}f^{\prime}(h^{\prime}) = (Y - o)W^{(2)}\sigma(h^{\prime})(1 - \sigma(h^{\prime}))\] \[\delta^h = (Y - o)W^{(2)}h(1-h)\]Update weights

After calculating the error terms at the output and hidden units, we can compute the gradients w.r.t weights and update these weights. The gradients are simply the error terms scaled by the input of the corresponding layer:

\[\nabla_{W^{(1)}}{L} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial{W^{(1)}}} = \delta^h\frac{\partial{h^{\prime}}}{\partial{W^{(1)}}} = \delta^hX\] \[\nabla_{W^{(2)}}{L} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial{W^{(2)}}} = \delta^o\frac{\partial o}{\partial{W^{(2)}}} = \delta^oh\]Now that we have the gradients, we can update the weights using the update step ($\eta$ is the learning rate):

\[W^{(1)} = W^{(1)} + \eta \cdot \frac{\nabla_{W^{(1)}}{L}} {N}\] \[W^{(2)} = W^{(2)} + \eta \cdot \frac{\nabla_{W^{(2)}}{L}} {N}\]There are two things to note here. The first is there is a $+$ instead of $-$. This is still the gradient descent because the negative sign is accomodated in the output error term $\delta^o$. Secondly, the loss is a mean over the records. This is why the gradient is downscaled by the factor $N$. In the case of batch training, $N$ is replaced by $m$ (batchsize).

Training

We have all the pieces of the puzzle and now it’s time to put everything together. We divide the training data into batches, do the forward pass, backpropagate to get the gradients and update the weights.

Hyperparameter tuning

We can tune the hyperparameters to improve the training performance. This can be done simply by changing the values and training to check the performance increase or decrease like below:

This can take a lot of time since we have no idea how to select the best configuration locally if we are trying out random values. Further, since these hyperparameters jointly determine the training performance, it is very hard to determine the optimal values. Instead, we use Grid Search to span over a range of values for each hyperparameter and train separately.

In this manner, we can locally get the best set of hyperparameters to fine tune our model.

Results

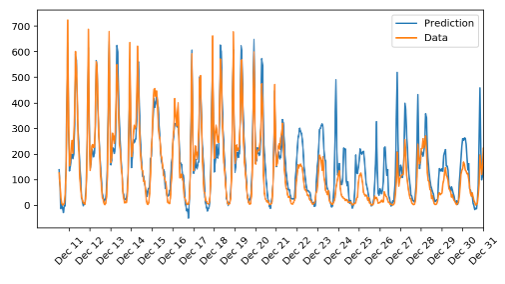

The model predicts the ridership data very well during Dec 11-Dec 21. After that, the prediction seems to follow the previous trend but diverges from the actual data. There is a plausible reason for this. The weekdays following Dec 22 are actually the holidays where the ridership will go down. But since this information is not present in the training data, the model follows the trend in the training data only and performs poorly during the holidays 🎅. This also makes sense why modeling the stock market is very hard.

Conclusion

In this extensive post, we came to know about the bits and pieces of training a neural network from scratch in NumPy. Moreover, we also studied the dataset and transformed the features. This started with identifying the target columns, converting the categorical columns to one-hot representation, dropping some irrelevant columns and finally normalizing the input features. For the network, we created a 2-layer perceptron and initialized its weights using a normal distribution. Then, we worked out the forward pass and backward pass. The latter involving the backpropagation algorithm. From there, we computed the update equation used in gradient descent to modify our weights and put everything together in the training module. Finally, we looked into hyperparameter tuning and performing a grid search to select the best local set of hyperparameters that maximizes the performance of the model. Click here to access the jupyter notebook of this project.

I hope you learned a few things from this post. It always excites me to write something about what I am doing. The other posts in this 5-part series will follow soon. If you have some feedback or want to add something on this post, feel free to drop a comment below!

References

- Photo by Robert Bye on Unsplash

- Bike Sharing Dataset

- Udacity Deep Learning Nanodegree